Healthy Elections Project

About the author: Tom Westphal '21 was the student director for the Stanford-MIT Healthy Election Project. He is a currently pursuing a joint J.D. and MIP M.A. degree at Stanford University.

The Challenge

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic is profoundly disrupting many aspects of American life, including a fundamental pillar of our government: democratic elections. The virus emerged during the heart of the U.S. presidential election cycle, forcing many states to postpone their presidential primaries to buy time for election officials to adapt to the virus’ challenges. As I write this in the first week of September 2020, election administrators across the country are still scrambling to ensure the presidential election in November can be held in a way that both does not endanger voters’ health and does not disenfranchise disadvantaged voters.

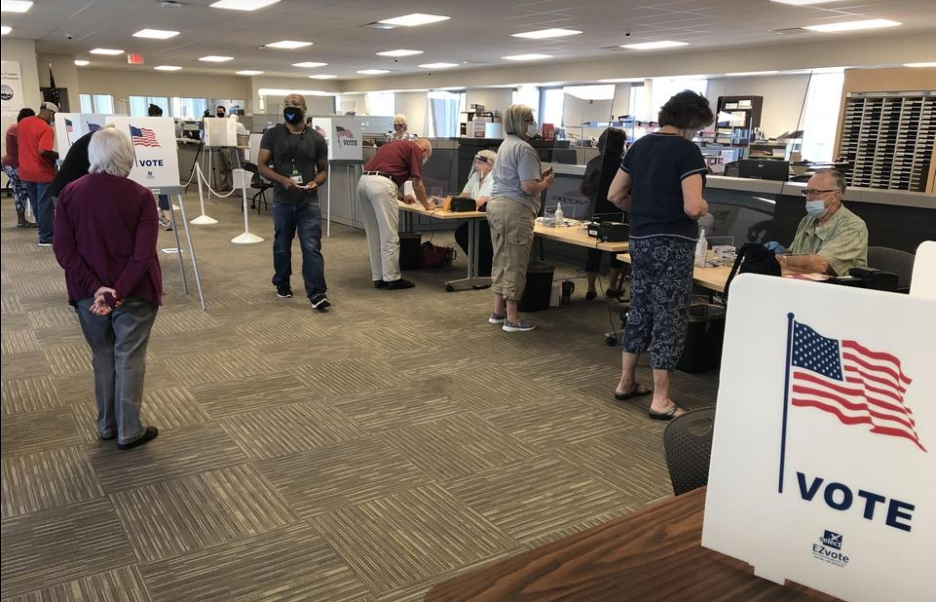

The exact mechanics of U.S. elections vary significantly from state-to-state, but historically most people in America have voted in-person, traveling to their local polling place to cast their ballot. These in-person polling places often feature crowded lines and require many people to touch shared surfaces, such as voting machines or polling booths, and therefore may be fertile ground for spreading the disease. To mitigate these vulnerabilities, election administrators have had to change or consolidate polling places, adjust voting procedures, and purchase vast amounts of sanitation supplies and personal protective equipment.

The pandemic has also created enormous poll worker recruitment shortfalls. Election administrators across the country rely on volunteer poll workers to staff polling places and deliver other key services. These volunteers are doing far more than simple administrative tasks—they are critical to the functioning of our democratic system. Recruiting enough volunteers is difficult, even in “normal” years. In 2016, a U.S. Election Assistance Commission survey found that two-thirds of America’s local jurisdictions couldn’t recruit enough poll workers for Election Day. And the volunteers that do show up are disproportionately older Americans—more than half of the country’s poll workers are over the age of 60.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has turned this problem into a full-blown crisis. Understandably, many older poll workers are declining to serve in such jobs because of the health risks. The problem touches every state in the country. In Florida’s March primary, for example, about 8% of the expected 4,800 poll workers did not show up in Miami-Dade County, forcing some polling places to open late and disrupting voting for some voters. During Wisconsin’s April primary, mass cancellations of poll workers contributed to Milwaukee shutting down 175 out of 180 of its polling places. Pennsylvania county officials recently voted to increase poll worker pay after election officials reported they were “beyond desperate” to recruit new workers. Georgia’s June primary, poll worker shortages contributed to long lines and a “spectacular collapse” of the voting process in some jurisdictions. Ninety-five percent of regular poll workers are declining to serve this year in Anchorage, Alaska. And other states were forced to postpone their primaries altogether, citing a lack of poll workers among their considerations. To combat these shortages, election officials must recruit hundreds of thousands of new poll workers before November.

In response, many states have drastically expanded access to voting by mail. But such expansion brings its own challenges. Vote-by-mail processes are more complex than many people realize, requiring significant investments in time and resources. Standing up entirely new processes, purchasing new equipment, and familiarizing voters with new procedures is a colossal administrative undertaking. And election officials also must grapple with shortages of specialized equipment. In vote-by-mail systems, election agencies often use automated mail sorters, digital scanners, envelope extractors, and signature verification technology to help process returned ballots. Such equipment can process ballots in a fraction of the time it would take to do so manually. But with every election agency in the country scrambling to procure automated equipment, manufacturers have struggled to produce and deliver enough machines to meet the surging demand. And the expenses of procuring new equipment comes at a time when the coronavirus’ economic impact has strained many state and local government budgets to the breaking point.

Stanford’s Response

Together, all these dynamics—adapting in-person voting to mitigate COVID’s risk, poll worker recruitment shortfalls, rapidly expanding voting by mail, difficulties in procuring new equipment, and others—have posed significant challenges to American election officials in preparing for a hotly-contested presidential election that is likely to feature record voter turnout.

In early April 2020, MIT professor Charles Steward and Stanford professor Nate Persily—both prominent election scholars--initiated a program to address the unprecedented and ongoing threat that the COVID-19 pandemic poses to the 2020 Election. Titled “The Stanford-MIT Healthy Election Project,” the effort sought to bring academics and election administration experts together to assess and promote best practices to ensure the 2020 election can proceed with integrity, safety, and equal access.

My work

I worked on the Healthy Election Project starting in April 2020, alongside spring MIP coursework, and continued through the summer. As the project’s student director, I helped grow the project to encompass the efforts of over 100 student volunteers. Under Prof. Persily’s direction, these volunteers documented the election preparations of key electoral battleground states and researched emerging problems in election administration. Working with local election officials and other partner organizations, we then compiled best practices and distribution our findings through a public-facing website (healthyelections.org).

Working at the Healthy Election Project was a rewarding way to spend my summer—I felt like I was making a significant contribution to making sure election officials got the help they need, and that our electoral system works for all voters. It provided real insight into how American elections work, and how America’s unique federalist structure impacts how local, state, and federal officials collaborate to tackle challenges like those posed by COVID-19. I owe a special thanks to Prof. Persily for including me in his work, which provided an amazing opportunity to apply what I learned in his courses to solving real-world policy problems.